Why the U.S. Mint Once Issued Gold Discs to Saudi Arabia

This blog post is a guest post on BullionStar’s Blog by the renowned blogger JP Koning who will be writing about monetary economics, central banking and gold. BullionStar does not endorse or oppose the opinions presented but encourages a healthy debate.

I stumbled on some strange gold discs earlier this year. They’re pictured below:

As you can see, the front of the gold disc has been stamped with the emblem of the U.S. Mint, specifically that of the Philadelphia mint. On the reverse side, contains details about weight and purity. But while they are shaped like a typical coin, the discs are curiously anonymous. Unlike a typical coin they have no date, denomination, issuing country, or the face of some dead President or royal. What are these odd discs and why were they produced?

My curiosity about these coins took me through on a fascinating tour of monetary history. Along the way I also learnt some troubling details about the coin collecting industry. The value of any coin is driven in part by its mythology, but this mythology is not always factual. In this post I’ll share what I learnt with you.

The ARAMCO connection

A quick Google search reveals all sorts of websites that sell the gold discs. APMEX, one of the world’s largest online precious metals dealer, describes them thusly:

“This Gold disk was made by the U.S. Mint in Philadelphia for ARAMCO (Arabian American Oil Company). ARAMCO needed them to pay royalties to Saudi Arabia for the right to start drilling for the vast oil reserves known to be there, and to help alleviate the shortage caused by the record consumption during World War II."

The reference to ARAMCO immediately jumps out. This is one of the most provocative and persistent details of the discs’ mythology: that they were produced for the Arabian American Oil Company, or ARAMCO, in the 1940s so that it could pay the Saudi government for oil. Comprised of a consortium of U.S. oil companies that included Standard Oil of California, Texaco, Exxon, and Mobil, ARAMCO explored and developed oilfields in Saudi Arabia.

The association of these disks with ARAMCO pops up everywhere on the internet. Heritage Auctions, the world’s largest collectible auctioneer, declares the discs to be “Aramco gold." The Deutsche Bundesbank, Germany’s central bank, recently added the discs to its 90,000 coin collection. It describes them as being struck by the U.S. Mint on “behalf of the Arabian American Oil Company."

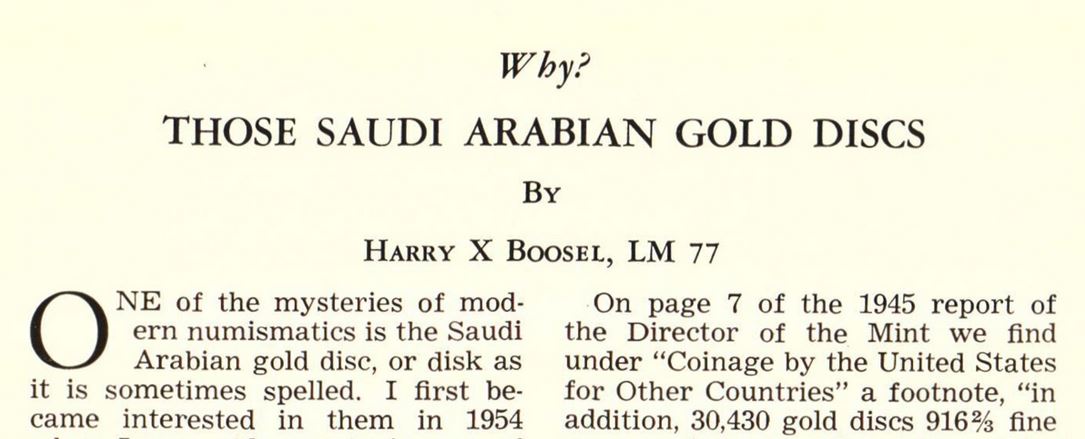

Boosel’s pet theory

The linkage of the discs to ARAMCO was first proposed in 1959 by numismatist Harry X. Boosel. Boosel’s curiosity was originally sparked when he bought one of the discs in 1954. He compiled a list of questions about the disc’s origins and diligently sent out letters to the U.S. Mint, the Saudi Arabian embassy, the State Department, and more. After he received several responses, Boosel penned a detailed article on the discs’ origins that was published in 1959 in The Numismatist, a publication by the American Numismatic Association.

Boosel learnt that the Philadelphia Mint had produced two types of discs. A larger one in 1945 contained 0.942 oz of gold, while the smaller 1947 version contained a quarter of that, 0.2354 ounces. The Mint had produced 91,210 of the original 1945 issue and 121,364 in the second batch.

The letters that Boosel received in response to his inquiries further indicated that the order had been filled by the U.S. Mint on behalf of the Saudi government. The gold had been purchased by the Saudis from the U.S. Treasury by converting U.S. dollars into gold at the statutory $35 rate. This was back when the U.S. was still on a gold standard and the gold window was still open. The gold in their possession, the Saudis had then asked the U.S. Mint to turn it into discs. This wasn’t the first order that the Mint had completed for Saudi Arabia, one of Boosel’s correspondents pointed out. It had previously produced silver riyal coins as well as copper “girshs".

But Boosel was annoyed. Although he had managed to fill in much of the detail surrounding the mysterious Saudi gold discs, he still didn’t know why they had been commissioned. His frustration was such that he concluded the paper by supplying his own pet theory, that the U.S. Mint had produced the discs for ARAMCO. Boosel tells us that gold was in short supply during and after the war, so it traded at a large–almost double!–premium to its official price of $35. Which is true. ARAMCO didn’t want to pay such a high price for gold, he claims, and thus went to Uncle Sam to get discs. Boosel provided no documents to back his contention.

Boosel’s shot-in-the dark ARAMCO theory has since gone on to become part of the accepted canon surrounding the discs. A 1991 New York Time article about the discs, for instance, notes that:

“Aramco sought help from the United States Government. Faced with the prospect of either a cutoff of substantial amounts of Middle Eastern oil or a huge increase in the price of Saudi crude, the Government minted 91,120 large gold disks adorned with the American eagle and the words “U.S. Mint — Philadelphia." Aramco paid for the minting and the bullion. The coins were shipped off to Saudi Arabia."

By the 2000s, coin retailing websites were eagerly repeating Boosel’s ARAMCO theory. Can you blame them? A tie-in with the oil industry spices up the discs’ history. And a provocative mythology can boost their market price. Although a 1945 disc contains just under an ounce of gold, it sells for US$2,749 on APMEX. A regular gold coin that contains one ounce of gold, say an American Eagle, currently retails for around US$1250. The market evidently attaches a very large premium to the rarity and unique history of the Saudi gold discs.

New documents surface

The ARAMCO story is certainly plausible, but I don’t think it is factual. The Federal Reserve Archival System for Economic Research, or FRASER, a relatively new archive, houses several documents that shed light on the discs, including a number of classified discussions between officials from the Federal Reserve and the U.S. Treasury about the gold market between the end of the war up till 1950. This information would not have been available to Boosel when he was doing his research.

Boosel is certainly correct that ARAMCO needed gold to pay for oil. When the Saudi monarch Ibn Saud and ARAMCO inked their deal in 1933, the terms of the deal stipulated that for each ton of oil produced, ARAMCO owed the Saudi government a royalty of four gold shillings. This amount was payable in gold sovereigns, a British coin that circulated widely in the Middle East at the time. Each sovereign contained 0.2354 ounces of gold.

The sovereign, however, had been discontinued. For the most part, the Brits had stopped minting these coins by 1917, and so their supply was limited. The FRASER documents provide us with several snapshots of ARAMCO desperately negotiating for old gold sovereigns. In 1948, it approached the Central Bank of Argentina with an offer to buy up its inventory of sovereigns1 while 1950 finds it knocking on the doors of the South African government to do the same.2

It seems logical, therefore, that in light of the rarity of sovereigns, ARAMCO might have contracted with the U.S. Treasury for gold discs. That the discs were stand-ins for sovereigns is underlined by the fact that the Philadelphia Mint had produced the 1947 issue with the exact same specifications as a British sovereign.3 Both sovereigns and discs contained 0.2354 ounces of gold and were of a fineness or purity of 0.9167.

Despite the attractiveness of Boosel’s ARAMCO theory, the FRASER documents do not bear it out. In each instance where discussions about the discs occur, they specify that the discs were made for the Saudi government, not ARAMCO.

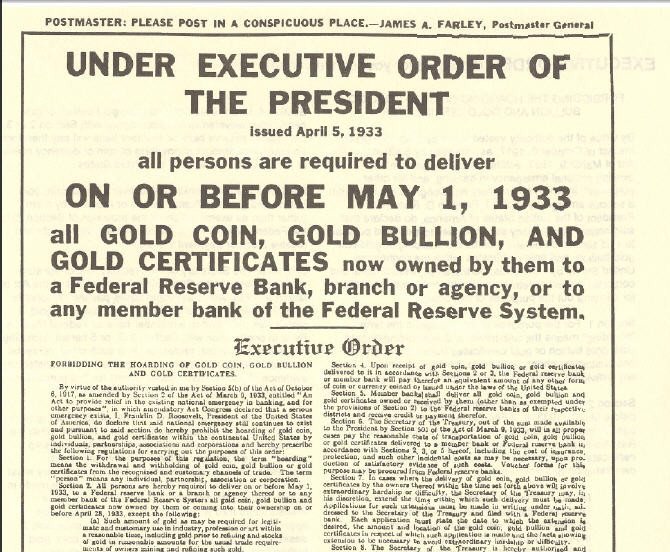

Boosel’s ARAMCO theory is even more unlikely given that the transaction would have been illegal. Under the rules governing the gold standard of the day, the Treasury was prohibited from selling gold to private companies. When the U.S. had gone back on the gold standard in 1934 after a hiatus beginning in 1933, the terms of redemption had been altered. Whereas everyone had historically had the right to convert U.S. dollars into gold, after 1934 only foreign governments were permitted to convert dollars into the yellow metal. Additionally, all U.S. gold coins were demonetized and private ownership of gold declared illegal.

So ARAMCO didn’t have the right to purchase gold from the Treasury. Not only that, but it would have been illegal for ARAMCO to store the discs on U.S. territory once received. One of the FRASER documents goes to great pains to point this out, noting that:

“It is the policy of the Treasury Department to sell monetary gold only to foreign governments and central banks and international monetary institutions. Accordingly… the Treasury did not sell gold to the Arabian American Oil Company or to any other unofficial purchaser."4

This isn’t to say that there was no connection at all between the Treasury and ARAMCO. The FRASER documents mention several instances of cooperation between the two. For instance, in 1948 the Treasury helped to facilitate $82 million in ARAMCO sovereign purchases by connecting it with foreign governments that held coin inventories (including the Argentinean deal mentioned above).5 But the Treasury only pointed ARAMCO in the right direction, it didn’t actually participate in the deal itself.

Walter Spahr and the Gold Standard League

Even when it was acting as a liaison for ARAMCO, the Treasury was reticent of the role it was playing. There was ongoing agitation to bring the U.S. back onto a full gold standard, one in which gold coins circulated once again and everyone–including American citizens–could convert paper money into gold. The movement was led by the feisty Walter Spahr, a New York-based economist who was the guiding light behind the Gold Standard League and its associated organization the Economists’ National Committee for Monetary Policy.

The Treasury, which had banned gold coins from circulation only eleven years before, feared Spahr and his ideas.6 By minting coins for foreign governments and helping companies purchase sovereigns, the Treasury risked drawing Spahr’s anger, providing him with the sort of fuel that he required to spark a public debate on the issue of gold coinage. Luckily for the Treasury, neither the Aramco sovereigns nor the coins sold directly to Saudi Arabia attracted Spahr’s attention or generated public complaints. “Skillful handling of reporters no doubt helped head off the chance of embarrassment," wrote one official.7

To sum up, it is doubtful that the discs were made for ARAMCO – if they had, the Treasury would have been breaking the law. The idea that the U.S. might have chosen to illegally issue the discs is even more unlikely given that government officials were sensitive to any sort of criticism in light of public agitation for a return to a pre-1934 gold standard.

A nation reliant on discontinued foreign gold coins

There is a much easier answer to Boosel’s frustrated plea for “the Why" behind the discs. Like most nations in the Middle East, Saudi Arabia didn’t have its own banknotes. Its monetary system was entirely reliant on precious metals coins. But it didn’t produce its own coinage. For smaller transactions, Saudis relied primarily on foreign silver coins including the ubiquitous Maria Theresa dollar, a coin minted in Austria. The Indian rupee, which circulated widely in the Middle East, was equally important. For larger exchanges, Saudis used British gold sovereigns.

It therefore made perfect sense for the Saudi government to call upon the U.S. Treasury for help. As I pointed out earlier, the Brits no longer made sovereigns. Given the inevitable shortage this must have caused, Saudi officials would have been desperate to supply the nation with a workable gold substitute for circulation within national borders. Turning to the U.S. made sense. The U.S. Treasury was the largest owner of gold in the world, and the U.S. Mint could turn this gold into coins. Unfortunately for the Saudis, British officials had refused to release the original dies for making sovereigns to the U.S. Mint.8 The unadorned discs that the Mint offered to produce in their place were thus a decent second-best option for the Saudi government. Apart from their markings, the discs were exactly similar to sovereigns.

After filling the 1945 and 1947 orders for gold discs, in October 1947 the U.S. Mint received a third order from the Saudi government. But the Saudis ended up cancelling this order in light of a superior proposal. That December, U.S. officials indicated to the Saudis that the Treasury would be willing to auction off old British sovereigns that it held in its official reserves.9 For the Saudis, this offer of actual sovereigns was too good to pass up, so they nixed the third issue of discs and took delivery of sovereigns instead.10

In Conclusion

The ARAMCO gold disc story is apocryphal, a bit of idle speculation first dreamt up fifty years ago and recounted often enough to be accepted as gospel. If anything, I hope that my account convinces gold coin buyers to do their homework. Anyone who is planning on purchasing a gold coin at a large premium to its commodity value needs to be sure they know exactly why they’re paying such a high price. Otherwise, best to stick to regular gold bullion coins.

The story of the Saudi gold discs also illustrates the bewildering variety of monetary arrangements that have existed across the globe, even within the same era. How strange is it that the U.S., which itself had banned gold coins only a few years before, found itself in the position of minting gold coins for a nation that was still wholly dependent on precious metals? Monetary systems are often full of surprises like this.

Footnotes:

1. Gold Transactions : 1949. Pg. 79

2. Gold Transactions : 1950. Pg. 12

3. ibid, Pg. 87.

4. Gold Transactions : 1949. Pg. 79

5. Gold Transactions : 1950. Pg. 52

6. ibid. Pg. 88.

7. ibid. Pg. 54.

8. ibid. Pg. 88.

9. ibid. Pg. 87.

10. Document 931

References:

1. United States. Department of the Treasury. Gold Transactions : 1950, Box 18, Folder 11, William McChesney Martin, Jr., Papers. https://fraser.stlouisfed.org/archival/1341/item/472983, accessed on November 24, 2018.

2. National Advisory Council on International Monetary and Financial Problems (U.S.). Gold Transactions : 1949, Box 18, Folder 10, William McChesney Martin, Jr., Papers. https://fraser.stlouisfed.org/archival/1341/item/472982

3. Foreign Relations of the United States, 1947, The Near East and Africa, Volume V Document 931. https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1947v05/d930

4. Eric P. Newman Library, Harry X. Boosel Correspondence File, 1954-2001. https://archive.org/details/booselharry1954to2001epncorr

Popular Blog Posts by JP Koning

How Mints Will Be Affected by Surging Bullion Coin Demand

How Mints Will Be Affected by Surging Bullion Coin Demand

Banknotes and Coronavirus

Banknotes and Coronavirus

Gold Confiscation – Can It Happen Again?

Gold Confiscation – Can It Happen Again?

Eight Centuries of Interest Rates

Eight Centuries of Interest Rates

The Shrinking Window For Anonymous Exchange

The Shrinking Window For Anonymous Exchange

A New Era of Digital Gold Payment Systems?

A New Era of Digital Gold Payment Systems?

Life Under a Gold Standard

Life Under a Gold Standard

Why Are Gold & Bonds Rising Together?

Why Are Gold & Bonds Rising Together?

Does Anyone Use the IMF’s SDR?

Does Anyone Use the IMF’s SDR?

HyperBitcoinization

HyperBitcoinization

JP Koning

JP Koning 12 Comments

12 Comments