Life Under a Gold Standard

What would it be like living under a gold standard?

Here are a few (but by no means all) of the features that would characterize it:

- Banknotes, up until now irredeemable, would be convertible into gold. Bank deposits might also be convertible into gold.

- The general level of consumer prices would be determined by the gold market, and not central bank policy. Which means that prices would no longer perpetually rise each year.

- The gold market is unpredictable, however. And so from one year to the next, the movement of consumer prices would also be unpredictable.

- Finally, something called Gibson’s paradox would re-emerge. (I’ll get into the specifics of this later on in this post).

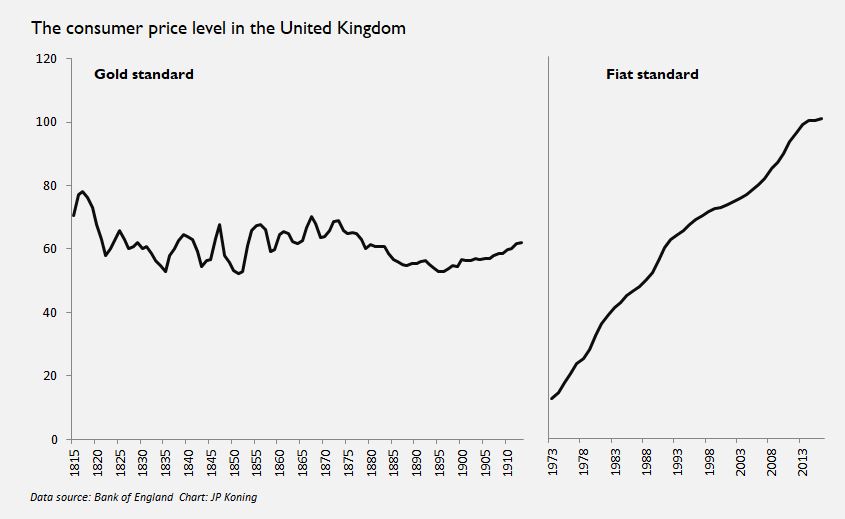

Different types of price stability

The best way to illustrate some of the features of life under a gold standard is by reference to an historical illustration. On the chart below at left, you can see how consumer prices acted in the UK during the classical gold standard, which operated between 1815 and 1914. On the right, I show how consumer prices in the UK behaved from the end of the Bretton Woods system in the early 1970s until now, when the nation was on a fiat standard.

As these charts illustrate, economic life under each system is quite different. On the UK’s current fiat standard, consumers know that prices will always rise over time. They also know that the rate at which prices increase will be fairly uniform from year-to-year. 2%. 2.5%. 3.1%. 1.1%.

Granted, during the inflationary 1970s, prices did have a tendency to rise quite fast. (In 1975, they jumped by 23%!) Over the last four decades since then, however, British consumers have been fairly confident that they will be paying around 1% to 5% more each year to maintain their living standards.

On a gold standard, UK consumers had a different sort of clarity. Unlike modern consumers, they knew that prices five or ten years in the future would be about the same as the present. If a steak dinner cost 50 pence today, it would probably cost about that in the next decade.

On the other hand, Brits living on a gold standard had much less certainty about where prices would be next year compared to modern day Brits. We know that if a steak dinner costs us £10 in 2019, it’ll probably cost around £10.50 in 2020 and £11 in 2020. In 1847, however, the general level consumer prices rose by 7%. The next year prices fell by 14%! So a steak dinner’s price from 1846 to 1848 would have been quite variable. That sort of short-to-medium term volatility isn’t something that the modern consumer is familiar with.

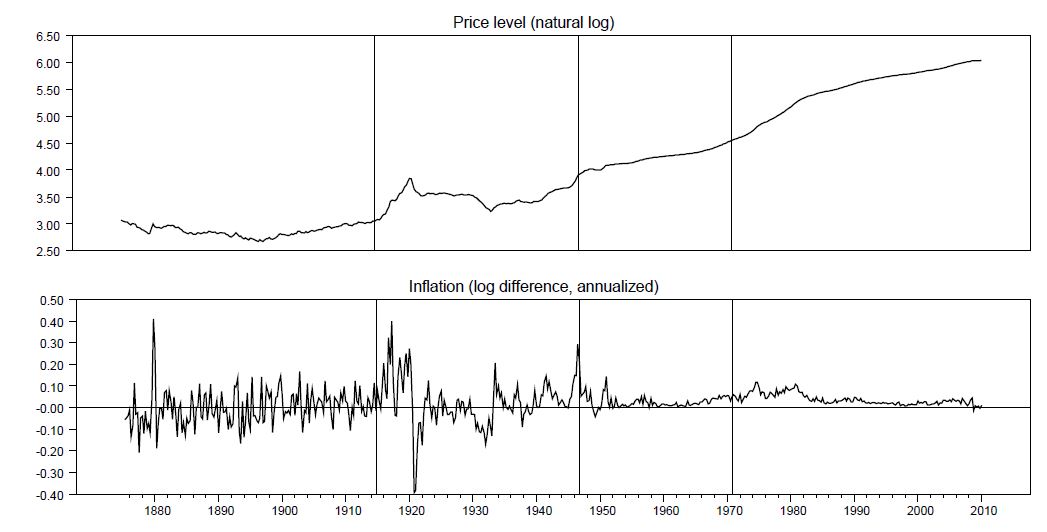

The U.S. displays the same pattern as the UK. Below is a chart showing the US price level and inflation rate from 1875 to 2010.

On the other hand, U.S. gold standard-era prices showed remarkable long term stability. In 1913, the price level was roughly the same level as in 1875 (see top panel). By comparison, over the fiat era the U.S. price level has consistently risen.

Flexible vs rigid

So why do fiat and gold standard systems show such different patterns? The answer has to do with how flexible these systems are.

Say that the public suddenly wants to hold more money. Under a fiat standard, central banks can rapidly create as much banknotes and reserves as are required to satisfy that demand. And once that demand contracts, they can quickly undo this by repurchasing unwanted notes and cancelling them.

Not so under a gold standard. If the public wants more gold, miners can’t simply produce more of the stuff. The only way for the economy to adjust to higher demand is for the price of gold to rise. And since under a gold standard everything is priced in terms of gold, that means the price of all consumer goods and services has to fall.

The same process works in reverse when the public wants less of the yellow metal. There is no mechanism to dematerialize gold. And so the way that the economy accommodates itself to a decline in gold demand is via a fall in the gold price, which translates into a rising price for consumer goods under a gold standard.

So in a nutshell, that’s why both the U.S. and UK price levels demonstrate such whipsaw patterns during their respective gold standard periods, but not their fiat periods. Fiat standards are better able to bend to constant fluctuations in the demand for money.

Which gets us to the last difference I wanted to highlight, something called Gibson’s paradox.

Gibson’s paradox

Under a fiat standard, there is no relationship between the interest rate and the level of prices. So for instance, the interest rate on bonds has generally fallen over the past twelve months. In the U.S.’s case, the ten year bond rate has gone from 3% to 1.5%. That doesn’t mean that we’d expect the prices we pay for groceries, housing, and entertainment to have fallen too. Like clockwork, prices always rise (in the U.S.’s case, by the same 1.5%-2% that they did in previous years).

But under the gold standard, we would expect interest rates and the general level of prices to fall together. So if interest rates on bonds were to fall from 3% to 1.5%, we’d also expect the overall prices of things like food to decline in concert.

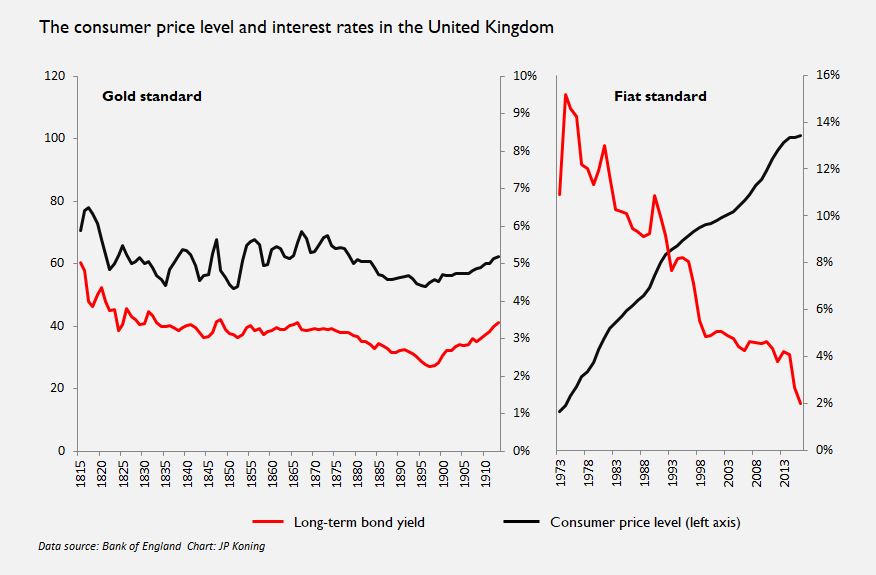

The chart below shows this phenomenon.

During the UK’s gold standard period which lasted from 1815 to 1913, the general level of consumer prices tended to fall and rise along with the long-term government bond rate. See chart at left. The lines sync over both the short and long-term.

But during the UK’s fiat period (pictured at right) there is no relationship at all between the two. Alfred Gibson, a banker, initially noticed the co-movement of prices and rates in a 1923 issue of Bankers’ Magazine. Later on, John Maynard Keynes described the paradox as “one of the most completely established empirical facts within the whole field of quantitative economics."

What explains Gibson’s paradox?

Gold as a durable real asset

Gold is a long-lived asset that competes with other assets and capital. Instead of holding a gold bar, one can also buy real estate, or invest in a bond, or buy shares in a company.

If the world becomes less fruitful and projects are no longer as profitable as before, then the expected return on assets like bonds will fall. Bonds, which are fixed claims on projects, simply can’t provide as much interest as they did in a more productive world. But when this happens, gold becomes more competitive with bonds. Gold’s lack of interest becomes less of a handicap than it previously was. And so investors want to hold more gold, which means that the price of the yellow metal rises.

In the 1800s and early 1900s, this rise in the price of gold caused a fall in consumer prices. After all, under a gold standard every consumer good is priced in terms of gold. And that’s why Gibson observed that interest rates and the general level of consumer prices moved together under a gold standard.

To sum up Gibson’s paradox, when the general pace of economic advancement slows: 1) bonds yield less interest, and 2) gold becomes more competitive, and thus 3) consumer prices (which are set in gold) fall. Conversely, when the economy becomes more productive: 1) bonds yield more interest, and 2) gold becomes less competitive, and so 3) the prices of food, shelter, and other consumer goods and services rise.

On a fiat standard, gold has ceased to be the fulcrum around which all prices rotate, so Gibson’s paradox no longer appears. Even during the worst downturns, say like the 2008 collapse, bond prices plunged but core consumer prices continued to reliably rise by 1-2%.*

* Robert Barsky and Larry Summers were the first to explain Gibson’s paradox as a function of gold being valued as a durable real asset. The paper is here.

Popular Blog Posts by JP Koning

How Mints Will Be Affected by Surging Bullion Coin Demand

How Mints Will Be Affected by Surging Bullion Coin Demand

Banknotes and Coronavirus

Banknotes and Coronavirus

Gold Confiscation – Can It Happen Again?

Gold Confiscation – Can It Happen Again?

Eight Centuries of Interest Rates

Eight Centuries of Interest Rates

The Shrinking Window For Anonymous Exchange

The Shrinking Window For Anonymous Exchange

A New Era of Digital Gold Payment Systems?

A New Era of Digital Gold Payment Systems?

Life Under a Gold Standard

Life Under a Gold Standard

Why Are Gold & Bonds Rising Together?

Why Are Gold & Bonds Rising Together?

Does Anyone Use the IMF’s SDR?

Does Anyone Use the IMF’s SDR?

HyperBitcoinization

HyperBitcoinization

JP Koning

JP Koning 10 Comments

10 Comments