Gold Confiscation – Can It Happen Again?

This blog post is by blogger JP Koning. BullionStar does not endorse or oppose the opinions presented but encourages a healthy debate.

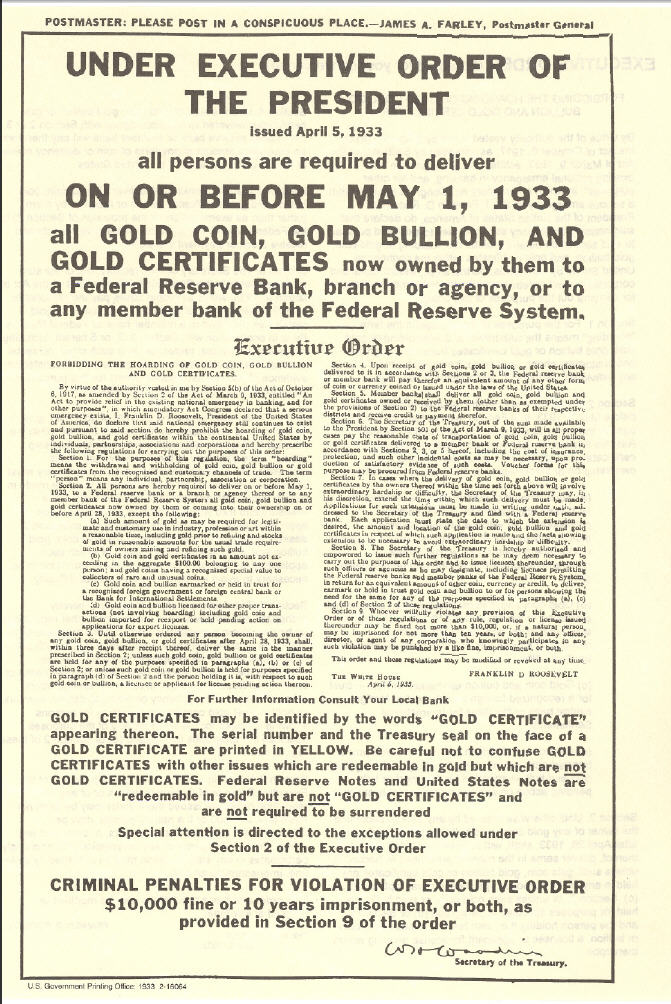

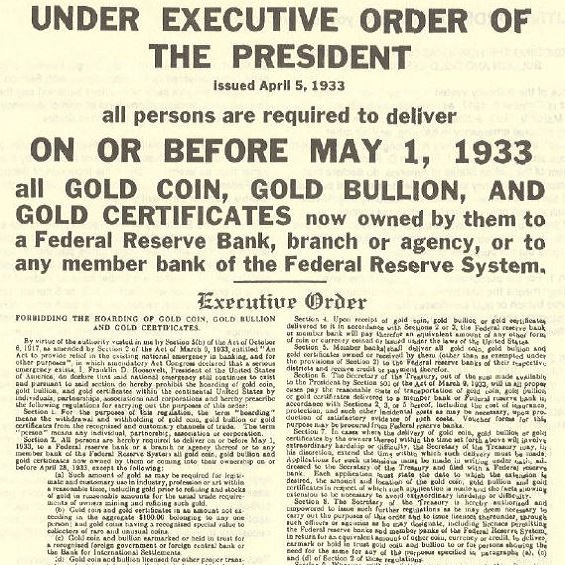

On April 5, 1933 a strange announcement appeared in U.S. newspapers. Thanks to Executive Order 6102, anyone living in the United States – citizen or foreigner – was required to turn in all gold bullion, gold coins, and gold certificates to the government before May 1, 1933. The same went for businesses and corporations.

This wasn’t an all-out confiscation of gold. Although people were obliged to bring their gold in, the government promised to pay the official price of $20.67 for each ounce submitted. However, violators could be imprisoned for up to ten years.

Executive Order 6102 included a few exceptions. Jewellery, industrial holdings such as dentist’s inventories of gold, and rare collectors coins were all exempt. Furthermore, the public could still own a token amount of the yellow metal (or gold certificates), up to $100. But for the most part, it was now illegal to hold gold in America.

These days, people who own gold often wonder if they might be subject to a repeat of April 5, 1933. Could a democratic government once again force its citizenry to give up their Gold Eagles and Krugerrands? Might people be required to sell their gold ETF units for dollars, or give up bullion stored in vaults for euros?

To properly appraise this risk, we need to understand why the US government did what it did. The simplest theory is that governments are inherently confiscatory. And so the April 1933 event could be replicated any day.

I disagree. The better explanation for why 1933 occurred spotlights the government’s special role as monetary authority. Viewed in this light, Executive Order 6102 was the government’s way of adjusting the monetary system, at the time a gold standard, to cope with extreme economic events. Since we are no longer on a gold standard, a repeat of April 1933 is unlikely.

The gold pivot

Prior to the Great Depression the world was on a gold standard. Every currency in the world was either defined as a certain amount of physical gold or pegged to another currency that had a gold definition, usually the U.S. dollar or the British pound.

As such, the market for gold was different from every other market. When the demand to hold copper increased, for instance, all that happened was that the price of copper rose. The same went for cars or houses or lettuce. But when the demand to hold gold increased, millions of other prices had to fall. Put differently, the global economy’s massive array of prices pivoted around one very special market, the gold market.

As unemployment exploded and prices collapsed through 1930 and 1931, nations such as Canada, Japan, Australia, the UK, and Sweden began to suspend their commitments to the gold pivot. They did this by ending their promise to convert their currencies into gold or gold-linked currencies. By severing the link between the gold market and prices, they hoped to dull some of the economic damage.

So when U.S. President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s announced in April 1933 that all gold held in the U.S. now had to be brought to the government, he was following a path already set by a long line of governments before him. Like his predecessors, he was trying to hack away at the gold market’s role as pivot.

Specifically, Roosevelt’s executive order decried “hoarding" or the withdrawal of gold from the “recognized and customary channels of trade." By transferring all of the nation’s gold to the government, he was hoping to exert more control over the gold market.

Today, gold no longer serves as a pivot point. We have been living in a fiat money world since 1968. Whereas gold was special in 1933, in 2020 it is pretty much like every other good in the economy. And so the grounds for a Roosevelt-style gold confiscation no longer exist. If governments around the world are facing a depression and are casting around for a monetary response, a gold-specific policy simply is not on their radar screens. They are more likely to try measures like quantitative easing or negative interest rates.

In short, don’t worry about a repeat of Roosevelt’s Executive Order 6102.

Did anyone listen to E.O. 6102?

In A Monetary History of the United States, economist Milton Friedman made an effort to measure how much gold coins were actually returned in response to Roosevelt’s executive order.

Prior to the announcement, some $571 million in U.S. gold coins were outstanding. By January 1934, official statistics recorded just $287 million gold coins still in circulation. So presumably $284 million in coins had been brought to the government in compliance with Executive Order 6102. According to Friedman, the monetary authorities attributed the unreturned $287 million portion to loss, destruction, exportation, and numismatic collections.

But using various interpolations, Friedman found that this probably wasn’t the case. Most of the $287 million had been retained illegally in private hands. This meant that the Executive Order had a compliance rate of just 50%.

It should be no surprise that compliance was so low. Gold coins are very easy to hide. Sending police out to search each nook and cranny of every house or yard would have been prohibitively expensive. However, there were a few prosecutions for illegal gold hoarding including the arrest of 13 individuals in 1939 for engaging in bootleg gold sales.

Interestingly, Roosevelt’s prohibitions on gold would continue on the books until they were finally repealed by President Gerald Ford in 1974.

UK’s Defence (Finance) Regulations of 1939

Roosevelt’s confiscation is the best-known example of a peace-time gold confiscation. But a similar policy was enacted by the UK during war-time.

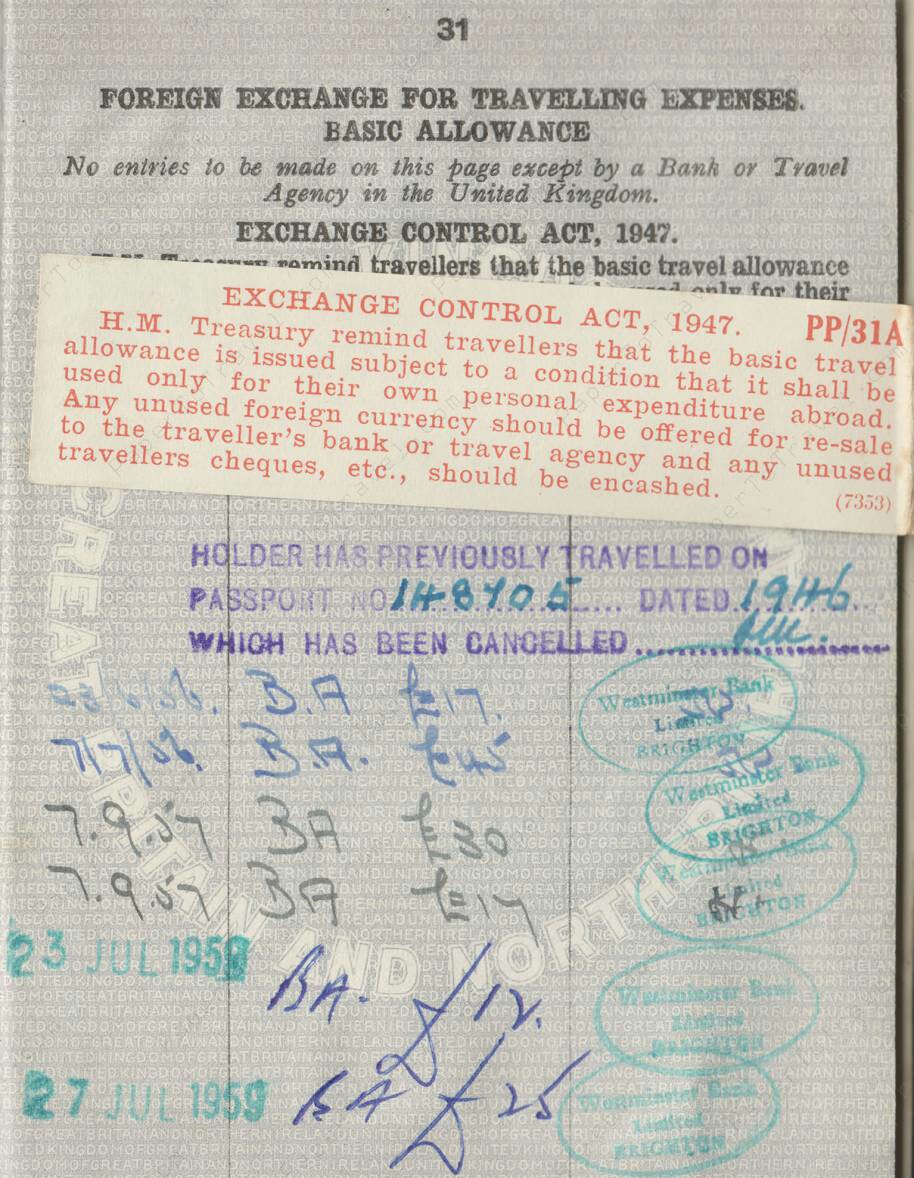

World War II began on September 1, 1939 when Germany invaded Poland. On September 3, the British government ordered all residents to “offer" gold coin and bullion to the Treasury. It also required them to submit certain types of foreign exchange, including U.S. dollars, Argentine pesos, Danish kroner, and Swiss francs. The Treasury was obligated to pay the market value for the instruments it seized.

Why did the UK Treasury take these measures?

To help drive the war effort, all sorts of resources would have to be diverted from public use. And so rationing of gasoline and food was quickly enacted. Foreign exchange was no different. To finance the war, Britain would need to buy ammunition and weapons from overseas. And to do so, it would need to have foreign exchange. Thus the requirement for the public to sell currencies like the dollar or gold to the Treasury. At the time gold was still a widely accepted international settlement asset.

These measures were formalized after the war in the Exchange Control Act of 1947. The stipulations concerning the legality of holding collectors coins was further fleshed out twenty years later. The Exchange Control Order of 1966 required that UK residents could only keep four gold coins minted after 1837. Anything in excess of that had to be surrendered for sale to an authorized dealer at a price authorized by the Bank of England.

The UK’s gold regulations were in some sense more restrictive than the American gold restrictions. According to law professor Arthur Nussbaum’s The Legal Status of Gold, whereas American restrictions did not apply to jewellery, the British Treasury’s rules applied to gold in all its forms, including vessels and chains. And while Roosevelt’s restriction didn’t apply to Americans’ overseas holdings of gold, the British restrictions applied to Britons’ overseas gold holdings too. (The U.S. regulations were stiffened in 1962 when President Kennedy declared that all overseas gold holding by U.S. citizens were illegal.)

On the other hand, the American law applied to foreign residents living in the US. But in the UK, foreigners were still allowed to buy and sell gold. This is why the London gold market was able to reemerge as the world’s most important gold market, even though Brits couldn’t buy and hold the stuff.

The UK’s exchange controls would finally be dismantled in 1979 under Margaret Thatcher.

Whereas the grounds for a Roosevelt-style gold confiscation no longer exist, a 1939-style British confiscation might. If World War III were to ever break out, it is conceivable that democratic governments might deem it necessary to requisition vital assets from the public. Even though gold is no longer a popular settlement asset, in a war scenario it might re-emerge as such. Or perhaps it might be seen as a necessary input for industrial purposes.

But if World War III breaks out, having some of our gold forcibly converted by our democratic government into fiat currency would probably be the least of our problems.

Popular Blog Posts by JP Koning

How Mints Will Be Affected by Surging Bullion Coin Demand

How Mints Will Be Affected by Surging Bullion Coin Demand

Banknotes and Coronavirus

Banknotes and Coronavirus

Gold Confiscation – Can It Happen Again?

Gold Confiscation – Can It Happen Again?

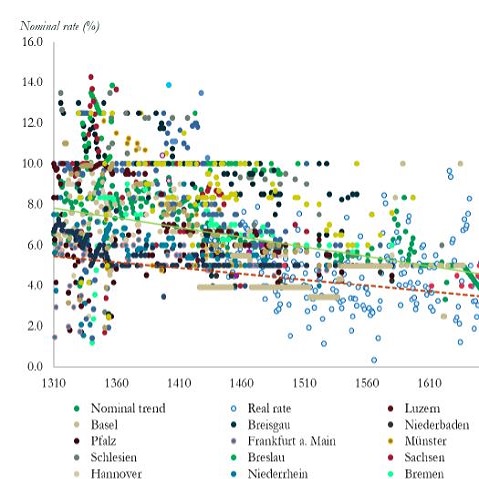

Eight Centuries of Interest Rates

Eight Centuries of Interest Rates

The Shrinking Window For Anonymous Exchange

The Shrinking Window For Anonymous Exchange

A New Era of Digital Gold Payment Systems?

A New Era of Digital Gold Payment Systems?

Life Under a Gold Standard

Life Under a Gold Standard

Why Are Gold & Bonds Rising Together?

Why Are Gold & Bonds Rising Together?

Does Anyone Use the IMF’s SDR?

Does Anyone Use the IMF’s SDR?

HyperBitcoinization

HyperBitcoinization

JP Koning

JP Koning 3 Comments

3 Comments